The Curious Case of Enterprise Infrastructure

Summary

After devolving into a reservoir of inefficient software and expensive hardware, the enterprise IT industry was unable to mount a defence to the onslaught of AWS. As a consequence developers and new enterprises are now going directly to the cloud. The former industry leader, VMware, has folded and repositioned itself as a gateway to AWS and steward of legacy workloads. The hosting industry is to a large extent following this example. While this is unfortunate for the enterprise industry, we claim that this also presents a market opportunity.

AWS has been growing exponentially for more than a decade now, but enterprise IT operations are not dead yet, what’s going on?

So, is enterprise IT a sinking ship, or even a collection of walking dead, as Wired put it in 2015 ? Many things have gone sideways in enterprise IT, but a major one is the inability of market incumbents to assemble any meaningful response to the onslaught of AWS. But here we are, 6 years on, and the cadaveric spasms seem to be dragging on for longer than expected. Anyone following this market has to be asking, what’s going on? Why has enterprise IT operations still not collapsed?

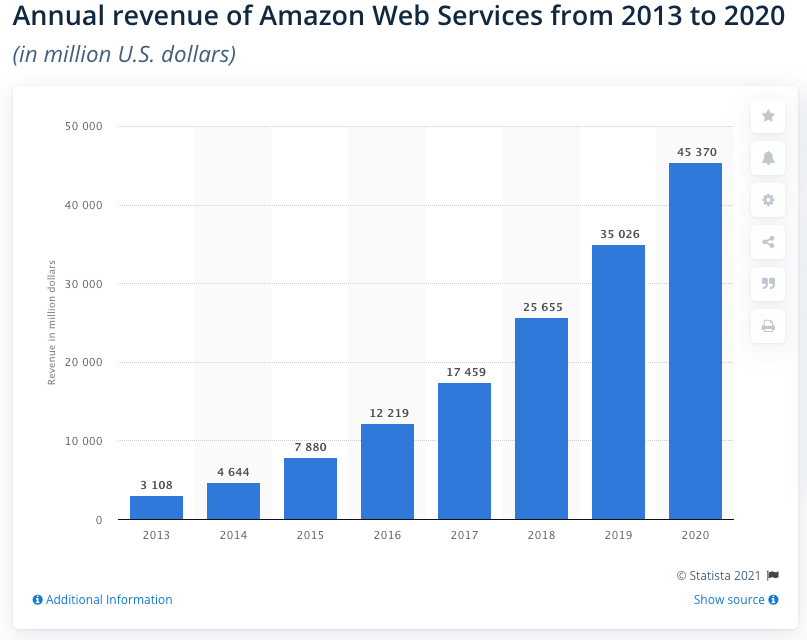

In my estimate, the addressable enterprise infrastructure market is currently a 110 billion USD market (see below). This is a very high-margin market, completely dominated and shared between incumbents like HPE, Dell, IBM, Cisco, Juniper, Lenovo, Microsoft, Oracle and VMware, in no particular order. The customers buying hardware and software from these vendors are the IT operations of companies and public institutions, as well as hosting providers. They use this hardware and software to run workloads like databases, web-, mail-, application- and file-servers in server rooms (AKA data centers). This market has shown a remarkable resilience in spite of the phenomenal rise of AWS and the other hyperscalers. AWS alone is now singlehandedly pulling in a remarkable 45 billion USD, all seemingly without putting a dent in the enterprise market, which remains surprisingly flat. I think it tells us several things: 1) Lift-and-shift operations of legacy workloads to AWS are failing or being abandoned, 2) Recoding of lecacy workloads as microservices is not really happening 3) New customers are going directly to AWS (no startups are establishing server rooms and hiring sysadmins).

To explain this, consider the fact that the legacy enterprise workloads running in enterprise server rooms, mostly consist of old Windows servers running old application software, and to a lesser extent ditto Linux/Unix servers. These are non-trivial to move to AWS or even Azure, and certainly require considerable man-power to do so. These workloads plus the odd new workload by existing enterprise clients, are what is keeping enterprise IT afloat, and maintaining a cash flow of over 100 billion USD from enterprises to the enterprise vendors. In my view no serious grab has been made for this market. All attention has been on lift-and-shifting workloads to AWS (and to a lesser extent Azure and Google), by consultants who actually have little to gain, once the operation is completed. Consultants generally have either strong legacy skills or strong cloud skills, but seldomly both. To complicate things further, they are typically dealing with operations teams, which for obvious reasons have very little to gain by helping.

Let’s dive a little deeper, and have a look at what is happening beneath the surface.

A market split in two

IaaS, infrastructure as a service, is a direct alternative to enterprise infrastructure in server rooms. The global IaaS market has almost overnight become a 50 billion USD market, heavily dominated by AWS. AWS did not use Microsoft, VMware, IBM, or Dell to build their stuff. They basically rode in on the back of commodity hardware, Linux, Open Source software, and built the rest themselves. We can assume that they initially bought some hardware for e.g. edge networking from Cisco, but today they most likely rely entirely on custom-built hardware delivered directly from the factories of China and Taiwan. They still buy CPU’s from Intel and AMD, but this is also changing fast. In short – AWS buys close to to zero from the incumbent enterprise vendors. This of course gives them a substantial price advantage, and has disrupted the enterprise infrastructure market. An estimated 20% of hardware sales is now going directly from Chinese and Taiwanese factories to AWS, Google, Facebook, et al. The “premium price for cutting-edge” narrative is falling apart. To explain why the enterprise incumbents have not yet seen a decline in sales, we posit that:

- The enterprise infrastructure customer base is static, and consists almost entirely of old legacy enterprises

- The enterprise vendors maintain revenue by increasing prices and because many of their customers are in fact growing

-

- Old, large enterprises have been steadily growing for decades, while there has been a global lack of new, large enterprises

-

- Existing customers are mostly unable to move their workloads to IaaS cloud providers because of various barriers

We also claim that old enterprises do not in general see their legacy IT infrastructure as a business advantage, on the contrary; almost all would prefer to get rid of enterprise IT operations. This essentially makes enterprise operations infrastructure a dead weight to legacy organizations. To explain why they are unable to shed this weight, we posit that:

- Legacy IT workers in general have neither the authority, the skills nor the motivation to move existing workloads to the cloud. They can however also not be fired, since they are needed to maintain the legacy infrastructure, which the enterprise depends on.

- Management typically hires external consultants to move legacy workloads to the cloud. The technical operations are not particularly complicated, but external consultants have little chance of success without support from legacy IT.

- For obvious (and sometimes even valid) reasons legacy IT often successfully puts up barriers to placing new workloads in the cloud (security, compliance, licensing, performance, cost).

So, while IaaS and enterprise IT operations serve similar purposes, they in fact serve fairly separate markets. The incumbent vendors of enterprise IT almost exclusively serve the IT operations of the incumbent enterprises of industry and the public sector, while AWS and the other IaaS cloud vendors serve cloud-native outfits, developers and start-ups.

To some extent the incumbent enterprise vendors have successfully defended a 100 billion USD market against the onslaught of AWS and the other IaaS vendors. Workloads started in enterprise server rooms are having a surprisingly hard time finding their way to the cloud, while workloads started in the cloud are not moving to the server room. The factors sustaining this situation may continue to do so for years or even decades. It is however a very precarious situation for the enterprise vendors. IT operations in enterprises are loosing ground, while application groups are gaining, and are showing enterprise IT operations very little love. If someone were able to offer a credible, workable path away from enterprise IT for enterprise workloads, most management teams would probably jump at the opportunity.

Why did enterprise IT vendors not engage AWS?

The incumbent enterprise vendors are companies like Intel, Cisco and VMware. Intel basically invented the modern CPU and server computing, Cisco basically invented IP routing, and VMware basically invented virtualization – the very fabrics of the Internet-based world we are all currently living in. Why are these incredible innovators seemingly sitting idly by, while AWS et al. are slowly eating their cake? It is of course complicated, but in essence it’s the old story of technology being comoditized, and startups becoming incumbents.

Mostly the efforts are forgotten today, but the enterprise IT industry actually tried to engage the cloud vendors, but simply failed. Oracle and IBM are still hanging in there, but basically there were a few lost battles, then the industry folded, and focused on protecting their existing turf. Small skirmishes are still breaking out now and then. In what looks like a small conflict by proxy, VMware is currently engaging Google by offering a path to running Google’s Kubernetes on top of legacy IT infrastructure. This is of course essentially the once-leader playing catch-up to the new cool kids on the block. Before Kubernetes, they tried offering OpenStack on top of VMware, and are even offering tools to run and manage VMware workloads on top of AWS infrastructure.

So while some of the incumbents were essential in creating the basic computing tech that runs the world, they were not so good at creating Internet services to run on top of this. The current standard enterprise infrastructure is simply put inefficient, compared to the one-stop IaaS (Infrastructure as a Service) provided by the cloud vendors (AWS, Microsoft, Google). Modern applications have basically outgrown enterprise IT. Add to this that the enterprise infrastructure stack (VMware, SANs, Windows Server, physical switches, backup, etc.) built to run ERP-systems, file servers, mail servers and databases, today is completely out of sync with the requirements of modern, scalable web applications (containers, CDN, DNS services, object storage). Some would argue that the infrastructure supporting the microservices of the day, is built using the good old enterprise building blocks. Unfortunately that is not the case – Amazon famously used commodity hardware and Open Source software to build AWS. Today they design and build their own hardware.

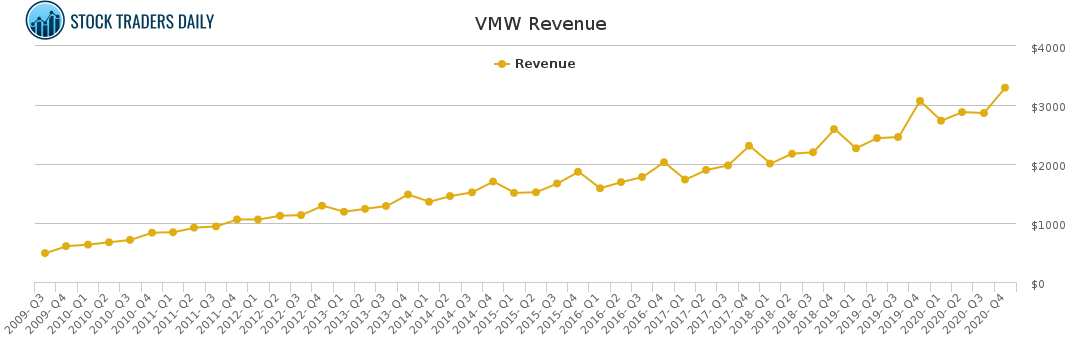

The edifice of AWS is undoubtedly one of the technological wonders of the modern world. It is a this point very, very hard to even start competing with AWS. Heck – they are even designing and building their own microprocessors. Even Google appears unable to compete. With that being said, there were many opportunities along the way, to prevent the current, in my view unfortunate, centralization of the data of the Western world in the hands of a few corporate entities. Before the rise of AWS, VMware was the undisputed leader of server management. VMware still runs an estimated 90% of the server rooms of the world, and has done so since their phenomenal rise in the late nineties. So when the rise of AWS began in earnest around 2010, the natural expectation of everyone in the industry was that VMware would provide their customers, enterprises and hosting providers, with capabilities similar to AWS, and some sort of balance would be achieved. I think no one expected that the lack of efficiency in enterprise computing was so utterly severe, as what was exposed by the rise of AWS built on commodity hardware and Linux. Least of all VMware. In 2013 the then COO of VMware Carl Eschenbach famously said to a group of peers: “I find it really hard to believe that we cannot collectively beat a company that sells books”. So – most waited for VMware to simply turn on “cloud” capabilities in their software, meaning giving hosting providers and other VMware customers a web UI, a REST API, and access to self-service provisioning of ressources, built-in billing, built-in monitoring, built-in backup, pre-packaged, useful virtual servers, heck – all the stuff any sensible IT operation could use. This did not happen. For precious years of AWS hypergrowth and innovation, VMware customers were stuck with a management UI running on Windows, old API’s, the usual license hell, while VMware (and the rest of the industry) went around belittling AWS. To add insult to injury they then gave us a Flash-based UI (yes, really) to offer clients as an IaaS offering from Hell. For years they tried improving the situation, by gluing various web interfaces onto their stuff and building new API’s, but it was all a bit of a disaster. They did indeed also establish a store for pre-packaged virtual servers, which was just not a good experience. No signs of tenant billing, monitoring, backup, patching, etc. in the core product – presumably to not alianate their trusted partners. They even tried building their own public cloud to compete directly with AWS, which quickly failed, and was sold for scrap value. In the end they folded and publicly commited to a future as a gateway to AWS, in essence choosing to become value-added AWS resellers.

So, that’s how we ended up with what are essentially two disjoint industries – an inefficient Windows-heavy industry running legacy applications in server rooms, and an efficient Linux-based cloud industry, running all the cool, new stuff in the cloud. They share a large technological heritage, but have surprisingly little real-world overlap. As always, there is a very large IT consulting industry, riding both horses, and making good money in the process. And caught in between is the once glorious hosting industry, which was given no tools to compete with AWS, but still has to pay the enterprise taxes.

What about Open Source?

AWS was built stringing together a patchwork of Open Source technologies, so why has the Open Source community not responded with something similar? you could ask. Primarily because it is a lot of work. This is basically why VMware has a business, after all. In fact this is also how VMware started – the original versions of their main product was built on Redhat Linux. In some ways VMware got bested by Amazon playing their own game. To be fair, there are a number of good and solid Open Source projects out there, but in the end, it just all sort of became a bit of a mess. The Open Source community pretty much put all their eggs in one basket, OpenStack. It started out with big hopes, dreams and money, the enterprise incumbents got in, and alas, conferences, consultants and corporate stuff ensued. I think most will agree that today there is not a simple way of establishing a local, private, multi-tenant cloud in the world of Open Source. We all wish there were, but there isn’t.

What about Europe?

The US tech sector has dominated the world for decades, and almost all of the incumbent enterprise IT vendors are american. As a natural continuation of this, the US cloud vendors simply continued this domination in Europe. But placing all the data, information infrastructure and basically all the inner workings of a modern society in the hands of a few large US corporations is a very different thing from just buying equipment and software. China and Russia realized this from the start, and have not allowed the US tech industry to take over their information infrastructure. Europe, being the military ally of the US has chosen a diffent path; a path of complete dependency on the US tech giants. This of course has absolutely enormous economic, social, political and even military consequences. This has finally dawned on the EU. Since the European private sector collectively does not seem to care one bit about simply paying, what in essence amounts to a cloud tax of billions of Euro each year to US corporations, in the great tradition of EU efficiency, the EU has decided to put an end to the dominance of AWS in Europe; enter Gaia-X (domain name is for some reason different than brand name), funded by the billions of Euros the EU has committed to The European Cloud Initiative, which is supposed to build a “federated cloud ecosystem”. To some this looks a bit like a repeat of a previous EU fiasco, but on a much larger scale. While waiting for Gaia-X to repel the Amazonians from the shores of Normandy, you could read this for a bit of counter-weight. The basic problem is of course, that Europe does not have much of a tech industry. OK, we do have ARM and Spotify, but when it comes to infrastructure it’s a bit of a wasteland. As stated above, this is to a large extent a consequence of history. Russia doesn’t have much of a tech sector either, but they do have a dictator hell-bent on keeping his country technologically independent. We don’t. China, well, they have both.

What about the hosting industry?

The only thing we have resembling a tech industry is what remains of the hosting industry. This industry was of course left hanging by the enterprise IT incumbents, whose technology their business was built on. Specifically of course VMware, who never delivered the self-service IaaS cloud software, that hosting companies were promised. Some parts of the industry are scrambling to stage a come-back (with the unavoidable setbacks), but a large part of the industry is slowly falling apart, torn between trying to slap a new label on their stuff, and sell enterprise infrastructure as cloud, or just simply folding and become AWS, Google and Azure resellers.

Market analysis

After all this doom and gloom, as promised, some good news. As established in the above, the situation appears to be the following:

- AWS owns the 50 billion USD IaaS market for workloads from cloud-natives, startups and developers

-

- The barrier to entry is high, but new entries to this market are still possible, as proven by Digital Ocean

- This absolutely requires the efficiency and low cost of Open Source, and is not possible using enterprise technology

-

- VMware still owns the 100+ billion USD market for legacy enterprise workloads

-

- No IaaS vendor has directly catered to this market so far

- Lift-and-shift operations are being driven by management hiring consultants and are largely failing

- Recoding of legacy applications is not happening much

-

The dynamics of the market are fascinating. Despite being proven hopelessly inefficient, enterprise technology still runs the majority of the world’s workloads. This means that this market is basically still wide open. One of the reasons for this is that lift-and-shift operations are very consultant-intensive, and are simply not very economically attractive to neither the enterprises, who see a large failure rate, nor the consultants, who see no sustained income after the lift-and-shift operation. Same goes for recoding/refactoring. Consultants generally move on, and leave the enterprises trying to run things in AWS with the same operations team, which then typically has to be expanded with AWS-savvy people. The hosting business, contrary to enterprise operations, have to make a profit in this new market reality. They have tried to solve this conundrum by offering lift-and-shift, not to their own datacenters, but to AWS. They offer this at a lower cost than the consultants, while taking over some of the daily operations from the enterprises. This generates some sustained income – in effect they become AWS resellers. This works for very few, and is no magic bullet. The problem of course being, that hosting industry workers do not become AWS experts overnight, and they still have to keep the lights on in their data centers. Add to this, that the 5-10% or so they can squeeze out of AWS or Azure, makes it very, very hard to make ends meet. To some extent they are being forced to saw the branch they are sitting on

The opportunity in the enterprise market is certainly there, but to successfully enter, a challenger would need to have an efficient IaaS offering. Not so much to offer customers, since they are often buying a managed service, but to have access to the implied efficiency and lower cost, and shed the weight of the enterprise tax. There is no other way to generate the necessary, sustained profit. This is probably some of the same conclusions IBM and Oracle have reached. Their problem being, that they are building their clouds with the exact enterprise tech, that AWS is already running circles around. A business able to offer a credible managed service offering built around an efficient IaaS infrastructure (built with Open Source and commodity hardware) could have a fighting chance in this market.

The doors in the cloud-natives, startups and developers market are on the other hand closing fast, with the rise of not only AWS, but also Azure and Google Cloud. However, the relative success of Digital Ocean, proves that challenging AWS for specific slices of the market is very much still possible. In Digital Ocean’s case, what they brought to the table compared to AWS and others, was initally simply fast storage in the form of locally attached SSD’s, which performance-wise ran circles around the traditional storage offered by AWS at the time, and which AWS had invested billions of dollars in. If anything, this proved that even AWS is vulnerable to innovation. To their credit AWS very quickly responded to the challenge. What Digital Ocean also brought, and still brings, to the table is a great user experience. They reacted to this challenge too, with Lightsail, but in my view failed. Simply put AWS did not win the market because of a great end-user experience, but because of the ineptness of the industry incumbents, the hosting industry, and their sustained focus on stability, predictable performance and aggressive pricing.

Currently the phenomenal rise of containers among the developer community and the somewhat unexpected complete domination of container operations by Kubernetes from Google, presents new opportunities to anyone looking to enter the IaaS market. These kind of disruptions will of course continue to pop up – that is thankfully still the nature of this industry. For now however, the market for enterprise workloads is in my view one of the biggest disruptable markets in the world. It may of course simply wind itself down over the next 20 or 30 years. AWS or Azure may launch a global consultancy and managed operations business, or new players may enter the field. In any case it will be interesting to follow.

What is “enterprise infrastructure”?

In this context, by “enterprise infrastructure” we mean the stuff that runs in the server rooms of the world, excluding the hyperscalers. Basically the hardware providing storage, networking and computing ressources, and the software orchestrating these ressources. The hardware is typically provided by different vendors – storage equipment (SAN’s, NAS’s) by EMC, Hitachi, Netapp, Fujitsu, et.al., networking equipment (switches, routers) by Cisco, Juniper, HP, Dell, et.all, and servers by HP, Dell, SuperMicro, Lenovo, et.al. They are of course all built to work together – switches route traffic to servers over ethernet, while servers in turn access storage over fibre channel, ethernet or just plain SAS. The software consists of an operating system running the servers (mostly Windows Server), virtualization software which allows running multiple operating systems (almost entirely VMware), and a large cesspool of supporting software for backup, service monitoring, reporting, registering and tracking software licenses, patching (i.e. upgrading software). Unlike hardware, operating systems and virtualization software, the supporting software cesspool is constantly changing. A special but very large niche is occupied by database software (almost entirely Oracle or Microsoft SQL Server) which of course also run on top of operating systems – they have their own cesspool of associated management software. Databases are important, but for the purpose of clarity, let’s leave them out of the equation for now.

The above has basically been the somewhat canonical infrastructure stack in enterprises since it was established in the late nineties. Formerly that is what all enterprises used to run on. Sure, they could choose between HP or Dell servers, but in general a they had to have a server room stuffed with all of the above (or rent space or ressources at a hosting center), and a team of IT workers to manage it. End user IT and server-side IT was in most organizations completely intermingled. Today, enterprises have the option of simply bypassing the above, and run their stuff in AWS. They still ned IT workers to manage this, but fewer, and they save on hardware and software.

How big is the addressable enterprise infrastructure market?

To be clear, what we are trying to estimate is the amount being spent directly on enterprise hardware and software necessary for maintaining server rooms at enterprises, or put another way, the amount an enterprise would save on hardware and software, if someone simply offered to move all their workloads somewhere else, so they could close their server room.

Let’s first look at hardware sales. Worldwide server sales were roughly 89 billion USD in 2020, enterprise storage sales were roughly 29 billion USD. Both are in decline – cloud providers are not making up for the decline in the enterprises, they are simply not buying enterprise hardware. The size of the global enterprise network equipment market is a bit harder to estimate, because enterprise switches are used both to provide connectivity between servers in the server rooms, and to provide network connectivity to end user devices. The total size appears to be roughly 40 billion USD. If we assume 25% of the switches handle traffic between servers, this market is about 10 billion USD. In total we are looking at an enterprise hardware infrastructure market of very roughly 128 billion USD in 2020. According to IDC, 21 billion USD of this hardware was purchased directly by cloud vendors (AWS et al.), not from HP, Dell, and those guys, but directly from Chinese and Taiwanese manufacturers like Quanta, Foxconn and Asrock. This number does not seem to include switches, but let’s assume it grew slightly in 2020, include ~5 billion in direct sales of switches to cloud providers, and we are looking at a global spend of roughly 100 billion USD on hardware from regular enterprises (including hosting providers). Even if this is probably in accelerating decline, it still dwarfs the hardware spend of cloud providers by a factor of 4 or 5, indicative of course of a massive mark up by the enterprise vendors.

Now let’s look at software. The boundaries are generally not very well defined, but since we are trying to assess the disruptable market size, for the purpose of this article, let’s define enterprise infrastructure sofware as all the commercial software which customers are paying for, that is not needed by enterprises that run exclusively in the cloud (i.e. does not own enterprise hardware). The main piece of software that is made redundant is of course VMware. To this we can add backup software. A lot of the supporting software like software for service monitoring, reporting, registering and tracking software licenses and patching (i.e. upgrading software), will most likely be made redundant by a move to a cloud provider, but for the sake of simplicity, let’s simply not include this in the calculation. To be fair – management will always require reports. VMware’s gross revenue in 2020 were roughly 10 billion USD, of which roughly 5 billion USD was revenue from software sales. To estimate the global enterprise backup market, let’s look at Veeam, who recorded sales of roughly 1 billion USD in 2020. According to themselves, they own 14.2% of the total market, which must then be around 7 billion USD. This also includes various desktop-related backup services, so let’s estimate the backup market to be around 5 billion USD. This puts the disruptable software market at around 10 billion USD, which compared to hardware sales is actually surprisingly low, while the margins are probably even higher.